It started in the year off 1899, in our small town of Austin, Indiana. The advances in canning technology — paired with the area’s rich soil and ideal climate — held the perfect environment for several young entrepreneurs to form the dream of building a canning plant. Unfortunately, one of those entrepreneurs didn’t quite have the money to buy the $500 worth of stock he wanted, so he offered to work off his debt by acting as president of the company. This young entrepreneur was none other than Joseph Steely (J.S.) Morgan. And thus started the history of the biggest and most influential companies of Austin.

Morgan Foods History

J.S. Morgan was married to Mollie Barrett Morgan, the only child of James and Elizabeth Barrett, who were among Austin’s earliest settlers. In 1820 a gentleman named David Washington Morgan (1775-1835), and his wife Sarah Hughbanks Morgan (1775-1844) arrived from Bourbon County, Kentucky, and settled in Scott County, Indiana, as one of the county’s early pioneers. A farmer, David and Sarah started their family and in 1825, a son was born which they named him, Nathan R. Morgan. Nathan too became a farmer but also operated a general store. Nathan and his second wife Mary Hughes Morgan shared seven children. In 1953 Dr. Carl Bogardus an Austin physician wrote a book about the early history of Austin, “Centennial History of Austin Scott County Indiana.” In the Bogardus book we learn that Joseph Steely Morgan (J.S.), the son of Nathan Morgan was born in Scott County Indiana, in 1858. Just after J.S. Morgan turned twenty years old, his father Nathan Morgan passed away in 1878.

Mollie was raised by her mother, as when she was just a baby her father James was killed in the Civil War fighting for the Union Army. James was part of the 35th Regiment, Indiana Infantry.

According to Bogardus, the first professional accounts of J.S. Morgan reveal he was a school teacher at a county school in Jennings Township, at a place called Possum Trot, which was about one-mile northeast of Austin. In 1881, J.S. opened a general store in North Austin which included a drug store, where he was the pharmacist.

When the Austin Canning Company was formed in 1899, a small group of local businessmen provided $500.00 each to start the business. J.S. was one of the original shareholders but since he did not have the funds to contribute, he was designated the company’s president for the first year, and his salary paid for his stock. J.S. Morgan was 41 years old and already established in the community when the Austin Canning Company opened for business. He was willing to risk it all for what he believed was an opportunity of a lifetime. In 1899, forty-one years old was considered old, and men were tired from a hard life of fighting to survive. Putting food on the table for family was one thing, but these were the days when America was on guard for one serious health threat after another, typhoid fever was a deadly killer feared by all.

The canning industry required long hard hours, and it was not a place for the timid. J.S. Morgan was not a timid man; he worked exhaustive hours with such a passion for his work he was viewed as obsessive by those who knew him best. In 1900, the company records show there were 75 employees in the first year of operation.

In the early 1900s when the operation was in jeopardy of shutting down J.S. started buying out his partners. For him failure was not an option and he wanted complete control of the thing that controlled his life, the canning company. He changed the company’s philosophy which was simple, out work the competitor, quit borrowing money to keep the operation going and make sure products were of the best quality. To ensure the quality of the products J.S. hired a quality inspector, himself. He personally wanted to guarantee the purity of his products. While he expanded operations, he vigorously perused the company books in search of cost savings that would prevent him from having to borrow money. One way he saved money was to do as many tasks of the company that he could possibly do, he was the President, timekeeper, quality inspector, purchasing agent, production supervisor and payroll administrator. He adamantly believed that borrowing money would be the ruination of a company.

Roadways presented serious transportation challenges. Before motor transportation was available, the company used the railroad or horse and mule teams pulling wagons to deliver their products. Bad weather presented an arduous task of traveling through slow and impassible roads. J.S. Morgan was not deterred by any of these events, he knew that if his products didn’t arrive on time customers would buy from another canner, and he would lose cash flow that would require him to seek credit. J.S. had an answer, he frequently employed himself as a driver of wagon teams to ensure timely delivery and to ensure cash returned safely back to Austin. He spent exhaustive hours milling farm lands that were growing crops for his company; he wanted his crops to look good in the fields which would provide better quality. It was a well-known fact that he spent almost 18 hours a day on the job, every day.

In the early 1900s America was changing over night with the industrialism of agriculture. Through industrialism farm land became an outdoor assembly line. Factory jobs changed rural America as people began to seek a more stable way of making a living. Instead of making their own food and clothes it was easier to let someone else make them, and then buy them. Farm work without modern equipment required the work of several hands on just a small farm, and even that did not guarantee an income. When Industrialism started America was willing to go to work for someone else and get paid for it.

During the industrialism of agriculture, the Austin Canning Company had one advantage that didn’t have anything to do with cash flow. The advantage was the prosperity of the tomato plant in Scott County. More tomatoes were produced in Scott County, than any other county in Indiana, and at the time Indiana was the leading grower of tomatoes in the United States. The tomato was an important factor of the early success of Morgan Packing Company, and J.S. Morgan saw an opportunity and planted more tomato crops than any other canner in Indiana.

J.S. Morgan and his wife Mary (Mollie) Barrett Morgan (1862-1951) were the parents of four children. Ivan Clarence Morgan, who later became commonly known as I.C. Morgan, was born on August 26th, 1880. Their first daughter Goldie Morgan was born in 1885 and two more daughters Lenora Morgan and Helen Morgan were born in 1896 and 1898.

Fifty plus years after his death the name I.C. Morgan is still a big name in Austin. There are many reasons for this, but none greater than his vision of a food canning empire and his commitment to expansion and new technology. Like his father he was extremely dedicated to the canning company, while J.S. was more focused on the day-to-day operation, I.C. was focused on the long-term opportunities for Morgan Packing Company in America. To execute his plan, he recruited people with experience in the canning industry and to deliver his products he developed the largest private-owned trucking fleet in the country. He wanted mass production, efficiency and the best quality for the Scott County name brand foods.

I.C. Morgan was born in Austin on August 26, 1880. He grew up happy and his days were filled hanging out at his father’s general store, where he ran errands by delivering medicine and food to people in the town. He liked delivering goods to his father’s customers and found he was a welcome visitor. Perhaps this is where he learned to talk to people and to take the time to understand them. Young I.C., also spent a lot of hours on the empty lots of Austin playing baseball with other kids, a sport he deeply loved.

The many hours he spent in the pharmacy of his father’s general store contributed to his strong interest in medicine. At an early age he told others he wanted to become a medical doctor. It has been said by many close to the family during this period that young I.C., was deeply disappointed that his father could not afford to send him to medical school. Instead I.C. attended one year of business school at the Indianapolis Business College, before returning to Austin to run the general store while J.S. Morgan ran the cannery.

In 1905, I.C. married Fern Harrod and their first child was born on April 6, 1905, a son, Ivan Harrod Morgan who became commonly known as Jack Morgan. I.C. and Fern would have two more children, one in 1910 a daughter Marion Morgan Lyons (1910-2004) and in 1913 another daughter Margaret Morgan Renard (1913-2004). (Fern Harrod’s father was C.F. Harrod, who was recognized as one of Austin’s most distinguished citizens. C.F. Harrod passed away in 1925.)

By 1907, I.C. was heavily involved with the cannery, his goal of becoming a doctor now forgotten. But he had held onto another one of his childhood dreams, baseball. I.C. brought professional baseball to Austin in the form of a semi-pro team that played in the Southern Indiana Baseball League for over 45 years. In the early days I.C. was a star player for the Austin Packers, the nickname Packers was given to the team after Morgan Packing Company. I.C. loved competition and sports seemed to be a perfect outlet for the rugged 6’2” two-hundred-pound man, which was considered a huge man for the early 1900s in the United States.

Don Garriott played for the Austin Packers in the 1930s and ’40s when I.C. was the coach, but remembers hearing that I.C. was a great player. “As an athlete I’m told I.C. was really ahead of his time. Guys that were old enough to remember him said that he could really play and was good enough to play in the majors.” Garriott added that I.C. recruited heavily for his baseball team, giving ballplayers year-round jobs if they would sign a contract to play for the Packers. “If you were really good, he’d find you a place to live and pay the rent, at one time he had about ten guys living in houses he owned for free.” I.C. loved baseball so much that in the early 1900s he built a small baseball stadium on property that adjoined the factory on the east side just across the railroad tracks (Later the American Can Company was built on this site). In the early 1920s he built another ballpark, that seated over 500 people just south of the plant’s main entrance and was the main attraction of Austin for many years. I.C. loved for employees of Morgan Packing Company to attend games and on many occasions, games were sold out. In 1934, I.C. paid outrageous wages for a big reputation pitcher named Hickory Ferrell, who led the Packers to the 1936 Southern Indiana League Championship. Ferrell and Morgan shared a love of competition, beyond baseball. The two men traveled across the United States on hunting trips where they engaged in fierce competition. They traveled to Philadelphia to watch a heavyweight championship fight that featured world champion Joe Louis.

The baseball stadium wasn’t the only thing I.C. Morgan built in Austin. In 1919 he built a beautiful mansion in the heart of Austin, and its uniqueness is still admired by travelers to the community. I.C. and his wife Fern loved their new home and made it the gathering place for all holidays and family functions. On many pleasant evenings I.C. and Fern could be seen sitting on the porch, which was connected to the west side of the mansion. In 1923, I.C. built his father J.S. Morgan a mansion similar to his, on the other side of the road from his home.

I.C. Morgan was a huge man and a rugged individual who loved the outdoors and his presence commanded respect. I.C. just didn’t have a dream of a food canning empire he was committed to it. It was his idea to expand operations and in the middle of the turbulent ’20’s his ideas became reality. Morgan Packing Company factories opened in nearby Indiana communities like Scottsburg, Edinburg, Columbus, Brownstown, Underwood, Redkey, Franklin, Converse, Leota and Little York. The Brownstown and Scottsburg plants produced both pumpkin and corn. The Columbus and Edinburg plants were mainly devoted to tomato products, while the Franklin plant produced beans and corn.

I.C. Morgan worked hard to convince his partner and father J.S. Morgan that mass production was the key to manufacturing success in America. In the 1930s industries across America adopted this concept which changed the way companies viewed maintenance and inventory levels. I.C. Morgan wanted preventive maintenance programs in place long before they were viewed as an industrial must. I.C. analyzed the operations much like J.S. had, only with a different perspective. J.S. searched for ways to cut back expenses while I.C. searched for ways to improve efficiencies by exposing deficiencies. He believed investment in new machinery protected the company from having to cutback operations due to mechanical failures. I.C. loved new technology and was willing to pay for it; he spent thousands of dollars replacing old machinery with new machinery.

In order to meet mass production demands I.C. invested in the Retort operation and in the 1930s there were over 200 retorts. All products with the exception of tomatoes were processed in live steam at temperatures over 240 degrees. By this time Morgan Packing Company was making a huge impact in homes across America. The company was shipping their Scott County Brand name to the east coast, deep into the south and all over the mid-west. In just a short time I.C. Morgan had taken Morgan Packing Company from an Indiana canner to a national canning empire.

As history indicates I.C. was deeply involved with the community of Austin. In the 1930s he built a huge dance hall in downtown Austin and provided weekend entertainment. He also built a huge cafeteria and offered meals at a very affordable price for Austin citizens and visitors. The cafeteria remained open for nearly 40 years, and during the pack season close to 2,000 people were served on a daily basis.

I.C. Morgan was a great man of character who did not drink alcohol or smoke cigarettes, but while he didn’t smoke, he often handed out packs of cigarettes to those who did. His generosity extended to the school systems, where he donated building materials for new schools and purchased books and athletic equipment. Former Austin High School Principal Leland Langdon, said in 1988, that I.C. was the most charismatic man he had ever known. “When he entered a room, everyone quit doing what they were doing, to see what he was doing,” added Langdon. And Don Garriott added in 2002, “I.C. knew his business, but he was willing to listen to others. That’s really what helped define him as a great person, he made others feel important.” There were no slow days for I.C. Morgan, his interests extended beyond business and even baseball. In 1932, he was named the head of the Indiana Republican Party State Committee.

I.C. liked to surprise people with his generosity as was the case in 1941. After a long Pack season and many long hours, he sent the entire Morgan Packing Company main office employees to Florida by train, for an all-expenses paid vacation. I.C. believed the future of Austin depended on Morgan Packing Company, and he donated lumber and materials to local business owners to help build newer buildings and churches near the downtown business area. Joe Shields was a 1948 Austin High School graduate who went to college and earned his degree at nearby Hanover College. Joe’s father Lloyd Shields, a local businessman was friends with I.C. Morgan, and Joe played for the Austin Packers baseball team while he was in high school. Joe has fond memories of I.C. Morgan. “He really cared about Austin and had a great interest in the community; he wanted good people to live here because he knew how important they were to the success of his company.” Shields also stated that I.C. had a special quality when it came to helping others. “He loved to help people, but back in those days’ people had a lot of pride and wanted to earn their way. So, when I.C. helped someone, he went out of his way to make them feel like he was helping them because they were partners and not because they needed a handout. A lot of people would have done anything for I.C. because they knew he was there for them.”

In the 1940s America ran into hard times again, this time World War II along with the threat of invasion by German leader Adolph Hitler, created a fear in America not experienced since the Civil War. American businesses were disrupted, and Morgan Packing Company was no exception. It had been many years since the company faced such dire financial circumstances. One problem was a depleted work force, most young men were sent off to defend the United States. In order to keep the cannery in operation I.C. sought profitable government contracts, which included making food for the Armed Forces. He lobbied as many political powers as he could, and eventually the company was awarded a huge contract. He was still faced with finding enough people to staff the operation. A lot of women from the community were already working at the plant, so I.C. turned to the government again, in what turned out to be one of the most interesting pieces of history in the town Austin.

As the war escalated, Prisoners of War (POWs) were sent to the United States and in some cases the POWs were loaned out to companies who had been granted government contracts. Morgan Packing Company was one of those companies and under the guard of the United States Army more than 1,500 German prisoners were stationed in Austin. During the World War II era there were three generations of Morgan’s working at the plant, J.S. Morgan, I.C. Morgan and I.C.’s son Jack Morgan. After the war the company rebounded again, and in the late forties Morgan Packing Company was the most stable canning company in Indiana.

In December of 1948, an aging and tired J.S. Morgan passed away, but soon the family was faced with another tragedy. On February 1, 1949 after feeling ill for several weeks I.C. Morgan suffered a cerebral hemorrhage at his mansion, and was rushed to a hospital in Louisville, Kentucky. For the next three weeks his condition weakened, and on February 26, 1949, I.C. Morgan took his last breath and perished into eternity. I.C.’s death was met immediately with mourning in the town of Austin, he was a man of great character and no one knew that better than the citizens of Austin who had been inspired by his commitment to the community on many occasions.

I.C. Morgan was a man who left an impression on those who knew him. Not just in Austin but across the United States. In the March 1949 issue, the National Trade Magazine published the following obituary.

“I.C. Morgan was a colorful man, whose competition for nearly forty years had driven many other vegetable canner to distraction or thereabouts; who revived the moribund town of Austin, where he was born and turned it into an industrial center; who made himself a power in the Republican Party affairs, who headed the largest one man canning enterprise ever built and made it make money. I.C. Morgan was a large man with a powerful personality, who neither drank nor smoke. The tern rugged individualist may well have been originated to apply to I.C. Morgan, a man who will be deeply missed.” (National Trade Magazine, 1949.)

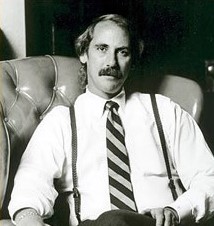

In this late 1940s photo I.C. Morgan (below) is pictured with his son Jack Morgan. This photo was taken just a few months before I.C.’s unexpected death. I.C. had been feeling ill for months but did not want anyone to know.

Ivan Harrod Morgan was born April 19, 1906 in a small white cottage in downtown Austin. The son of I.C. and Fern Morgan would become commonly known as Jack Morgan, and one of the most significant figures in the history of Scott County Indiana. Jack’s legacy remains strong in Austin, even though he passed away in 1985.

Jack Morgan’s distinguished career is defined like that of his father and grandfather, in that all three men rose to the occasion when similar companies were forced to close their doors due to poor economic conditions. Jack was no stranger to a good fight and there were many in his life. His battles with the Teamsters Union are legendary in Austin, as were his efforts to persuade town officials to incorporate and upgrade the town’s water and sewer systems. His greatest challenge however, was his fight against the worse economic time period in the modern era history of Scott County, which occurred in the late 1960s and early ’70s. With a determination exemplified by his predecessors I.C. Morgan and J.S. Morgan, Jack managed to keep the operations going at Morgan Packing Company, as he understood what the factory meant to his hometown, and perhaps his own legacy.

As a youngster Jack was well known in his hometown, he was constantly by his father I.C.’s side whether it was at the factory, a political rally or on the baseball field. Eager to learn about the plant at an early age, Jack would hang out in the company’s print and machine shops. He bragged to family and friends of the many tasks he performed at the plant. Jack delighted in spending as much time as he could with his father and the factory. During his days as a young boy, Jack and his two sisters Margaret (1911) and Marion (1913) would meet their father and grandfather for lunch almost every day.

Fern Morgan demanded that her children take education very seriously, and as a schoolteacher she devoted herself to their educational endeavors. Jack excelled as a student at Austin Elementary, but because Austin High School was not a fully commissioned high school, he attended Scottsburg High School in Scott County. When Jack graduated from high school in 1924, Purdue University in Indiana, with a strong reputation as the leading agricultural university in the United States is where he decided to attend college. While Jack understood the opportunities Purdue allowed him, West Lafayette, was not his kind of town. Before long he became unhappy and began to think about a place where his parents had taken him on vacation, sunny Southern California. A few months later he enrolled at the University of Southern California, where his Hollywood good looks and flamboyant personality seemed like a natural fit.

It is at USC, where he earned his degree and learned new methods for running a business. But when it came close for him to graduate some family and close family friends doubted whether the flamboyant Jack Morgan, would return to Austin. After all, his fast-paced life style seemed better suited for the West Coast, than the small town of Austin. And for a short period, he did pursue business interests in California, but eventually the lure of the Morgan Packing Company empire, snagged him back to his hometown. He also knew that joining the company would allow him to work side by side with the man he admired most, his father, I.C. Morgan.

When Jack returned to Austin from California, he received an uncommon amount of hype and attention from the small community. This type of attention would follow him for the rest of his life in the community, something that many believed he relished in. Tall, tanned, well-dressed, educated and remarkably handsome, Jack Morgan was ready to make his mark. He was eager to implement many of his new business ideas and he quickly earned the trust of his father, I.C. Morgan. I.C. thrust Jack into an important role with the company and put him in charge of the outside plant locations. Under Jack’s guidance the outside plants flourished, as he continued to learn the business from the man considered by many in the country as the best canner in America, his father. Jack was able to help build the company by using his education and relying on the vast knowledge of his father and grandfather. When it came to the operations side of the plant, Jack spent a lot of time on the floor learning from employees who were doing the jobs. Of course, Jack was very familiar with many of the processes, having grown up in the plant.

In the 1930s Morgan Packing Company was in the height of its glory, the company had become a national canning empire. The Austin plant now employed over 2,000 people, and a few of the outside plants were offering year-round employment. Jack was convinced that if each outside plant specialized on certain products, the Austin plant would be able to specialize in a variety of new products. Up to this point Morgan Packing Company was known primarily as a tomato and corn canning business. Under Jack’s guidance the company’s focus changed and the Austin plant began to produce ketchup, carrots, peas, lima beans, green beans, hominy, mixed vegetables and sauerkraut. In the 1930s Morgan Packing was the number one supplier of sauerkraut in the United States. With the outside plants producing corn, pumpkin and of course tomatoes the Austin plant continued to grow. But even with the success of the new products and the outside plants, the Austin plant still produced tomato products, as their number one item. Jack was committed to his father’s vision for Morgan Packing Company and he worked diligently with him.

An American Beauty

While the Scott County name brand products continued to be successful, Jack wanted a new name for the new products. His idea was to have a name that would catch the eyes of Americans looking for something new when they went to the grocery store; he decided to name the new products American Beauty. With Jack combining his talents as the company spokesperson, along with his business skills he successfully promoted the American Beauty label into the market, with fast and profitable returns. American Beauty products from Austin Indiana ended up in homes all across America, and Jack Morgan was making his mark.

American Can

Jack was instrumental in convincing the American Can Company to build a plant next to Morgan Packing Company in Austin. He wanted faster service of the cans he needed to run his operations. In 1936, The American Can set up shop on property sold to them by Jack. The American Can Company literally was constructed next door to Morgan’s, separated only by the railroad tracks. There were no shipping charges from the American Can to Morgan’s because there were no trucks needed. A catwalk was built over the railroad tracks which connected the two facilities, and inside the catwalk was a conveyor belt which transported the empty cans into the Morgan production area. Sometimes cans in carts were pushed over through the catwalk as well. Fourteen years after the American Can closed its doors in 1986; the catwalk still existed but was torn down in 2000. The American Can Company provided hundreds of well-paid jobs in the Scott County area and was vital to the local economy for over 50 years.

Elsinore Funk Morgan

(Below is Jack and Elsinore Morgan in the late 1930s)

In 1937 Jack married a stunningly beautiful woman named Elsinore Funk from Milltown, Indiana. The couple built a charming home just east of the Austin town limits and started their family with the birth of Ivan Edward Morgan in 1939. A daughter Michele Morgan was born in 1943 and a third child Diann was born in 1944. The last child of Jack and Elsinore was born in 1947, a son John Scott Morgan.

Elsinore was very involved with her children and shared her love of horses with them. She was a celebrated World Champion show rider and traveled across the United States competing in events. Her passion for horse show competition was shared by her children, and soon the Morgan children were also known as accomplished riders.

End of the 1930s

While Jack was establishing himself as one the nation’s prominent business leaders, he was also faced with a series of ugly and disruptive labor disputes in Austin. These disputes led to work stoppages which created intense and sometimes a series of dangerous events. With the small town closely connected to the factory, the labor disputes often created strong emotional bonds that often led to acts of violence towards the company. Jack however was not deterred and frequently battled union issues for the rest of his career, which many believe was a fight he enjoyed.

1940s

In the 1940s Jack Morgan was in charge of the company but he relied heavily on his father I.C. Morgan. With America in an economic slowdown and World War II fast approaching, Morgan Packing Company was suffering along with the rest of the country. When the war did start in 1944, many of the company’s employees were called to serve the country. While local women attempted to fill jobs and the company advertised across five states their intent to hire, there weren’t enough people to replace the vacancies.

In order to keep production going in factories across America like Morgan’s, the government decided to loan out prisoners of war for production work. I.C. Morgan lobbied political leaders for the use of German prisoners (POW’s) stationed in Camp Atterbury in Columbus Indiana. From August 1944 through April 1946, German POWs were stationed at POW Camp Austin just north of the factory on Morgan property. As many as 1,500 POWs were stationed there at one time.

While I.C. negotiated the agreement with the government for the service of the POWs it was Jack who was in charge of the operation. By the time the POW camp was inactivated near the end of the war, Camp Austin was rated as one the highest POW Camps in America. Jack established good relations with military personnel and the POW’s seemed to recognize his power. Even though the German POW’s seldom had contact with Jack they knew he was the guy running the show. They called him the “grob der chef” meaning Big Boss” or “grob Mann” meaning Big Man.

During World War II Morgan Packing Company reported profits despite the depletion of the local work force, this indicates that the POWs service at Morgan’s was well organized and very productive.

Don Garriott was employed at Morgan’s for over 40 years and was a company Vice President when he retired. Garriott noticed that Jack sought out information like no one he’d ever met. “Jack was known to ask a lot of questions, he wanted to make sure he had every piece of information available in order to make a decision. He was constantly thinking about the future of the company, he made the final decision, but he did seek a lot of information. Jack was the guy who made the decision there was doubt about that, but not before he asked a lot of questions.”

Culver Field worked for Morgan Foods for 65 years before he retired in 2002 and is the last person to have worked for the four generations of J.S. Morgan, I.C. Morgan, Jack Morgan and John Morgan. Field’s, too, remembered Jack’s penchant for information. “Jack knew he was going to make the final decision, so he asked a lot of questions. Sometimes he’d ask the same question over and over to make sure he got the same answer. Jack wanted to know everything; he didn’t want any surprises when it came to running his business.”

The Passing of Two Legends

In a period of three months, two of the most prominent and powerful men in the history of Scott County passed away. One was expected but the other came as a shock to the community and Morgan family. On December 21, 1948, the founder of the company J.S. Morgan, Jack’s grandfather passed away quietly at his home at the age of 90. Just three months later in February of 1949, I.C. Morgan suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and passed away at a hospital in Louisville Kentucky. The emotional strain on the Morgan family was overwhelming, and for Morgan Packing Company over 90 years of combined leadership had perished within 90 days.

Jack Morgan was just 43 years old and now solely in charge of one of the nation’s largest canning companies. The future of the company and in many ways the town of Austin was in his hands. Jack would face this challenge for the rest of his life, working to keep his grandfather’s company running and providing jobs for hundreds in Scott County.

1950s – New Modern Equipment – Same Old Labor Disputes

Once again manufacturing was changing in America with a wave of newer and faster machinery the food canning business was more competitive than ever. At the Chicago Machine Show in the 1950’s a new labeling machine caught the eye of Jack Morgan. “Jack was very excited about the new labeler,” remembered Don Craig a former Vice President of sales who retired in the mid 1990’s. “Jack told us the company would never be the same, no more labeling by hand, and by golly, he was right. We changed overnight.”

With the addition of new labeling lines Morgan Packing was labeling more cans than ever, which meant faster service to customers. The rail car business expanded after a slow period in the late 1940’s, and the company’s truck fleet was constantly on the go. Morgan Packing was picking up full steam when an old adversary slowed the company down again, labor disputes.

Over the years, Jack’s battles with the union have been scrutinized and told over and over in the small community, to the point where they have become a part of his legacy. By many accounts, Jack Morgan rather enjoyed his rivalry with the union. In November of 1954, the Teamsters (Truck Drivers) voted to strike at Morgan Packing Company, in what would lead to one of Indiana’s ugliest union disputes. While the truckers went on strike, the rest of the plant attempted to operate as normal. Jack Morgan decided to use a group of private truckers to haul the company’s products. As tensions mounted, the worse was inevitable as a series of dynamite incidents kept the small community on edge.

First there was a blast that blew open water lines halting production. Before long other blasts occurred to cars, railroad switches and to trucks hauling Morgan products. Fights broke out at the picket lines; gunshots could be heard being fired at the walls of company buildings all hours of the day and night. Private truckers were threatened; Austin was the focus of media all across the state, the publicity of the town was not positive. Indianapolis papers portrayed the town as down trodden, and a town ran by a bunch of roughens. As much as Jack was at odds with the strikers, he didn’t like the way the town of Austin was being portrayed in newspapers across the state. He used his influence to have articles re-written and the image of Austin re-painted. A Jefferson County, Indiana, paper used the term “Pistol City” to describe Austin. The unpopular nickname is sometimes still used, by outsiders of the community today. Indiana Governor George N. Craig ordered the Indiana State Police to Austin, where they were stationed for weeks. Craig also made several statements to the media in support of Jack Morgan. The Indianapolis Star put up reporters in hotels in nearby Scottsburg; the events of the day were reported daily. Not to be outdone by all the media hoopla and finagling of the striking truckers, Jack Morgan pulled some strings of his own.

The following story has been told by several different people in a very similar manner. By all accounts of the story, Jack Morgan decided it was time to take matters in his own hands. Private truckers out of fear had quit coming to the plant, to pick up goods during the strike. One morning it was reported to Jack, that several truckers waited in nearby Seymour, Indiana, to hear if they could go to Morgan’s without incident. Jack then went to the company garage, and he drove a truck and empty trailer out the gate to Seymour. Once he arrived in Seymour, he did not tell the concerned truckers he was Jack Morgan, instead he portrayed himself to be a truck driver. Jack led them to believe that he had already been to Morgan’s earlier, and picked up a load without any trouble. He enticed them, by saying he was going back for another load and they should come too. Encouraged the private truckers listened as Jack told them, stay in single file and do not to stop for anyone at the picket lines. A short time later with Jack in the lead and nine trucks following him, they barreled through the gate inside the plant. Once they were loaded, including Jack’s truck, he led them back out the gate. With a shotgun in the front seat, Jack waved to the angry striking truckers who recognized him. Don Craig remembered the incident, “Jack Morgan wasn’t afraid of anyone, he loved a good fight. Jack said that around Crothersville he saw some strikers in cars trying to get around the trucks, but the truckers squeezed them off the road. I don’t think those other truckers ever did realize he was Jack Morgan.” In January of 1955 the contract was settled, and peace was restored in Austin, Indiana.

1960s

Jack Morgan was now bigger than ever in the town of Austin. Jack not only owned the huge canning company, he owned several impact businesses in Austin such as a gas station, the largest supermarket in town, a Dairy Queen, and the town bank. Jack also owned the utility company that supplied water to both company and community, something he provided for free to the towns people. There was a huge cattle farm which was horseshoed around the outskirts of Austin. All his hard work was certainly paying off.

Of all the trials and tribulations that Jack Morgan had endured, none prepared him for the hardest and most trying time of his life. In 1964, Jack’s oldest son Ivan, just 25 years old took his own life at his apartment in Louisville, Kentucky in what was reported as an accidental overdose. Jack Morgan and his family were devastated. Deeply hurt, it was weeks before Jack returned to his office at company headquarters.

The 1960s were also a challenging time for the company; production was slowed by Mother Nature as droughts affected several pack seasons. The existing outside seasonal plants were becoming huge financial burdens, in both maintenance and taxes. The tomato and pumpkin market was also changing. For years Indiana had a stronghold on the tomato market, which greatly benefited a company like Morgan’s. A tomato first produced at Purdue University, and called the “Epic” would eventually lead to the demise of Indiana’s stronghold on the tomato market. This tomato favored the California climate and was capable of being mechanically picked. Since that time, California has out produced all other states in tomatoes.

To make matters worse for Morgan’s, a huge fire occurred at the main warehouse in 1967, threatening the entire facility. Fortunately, no one was hurt but the company lost millions.

Morgan’s Grocery Store and Cafeteria

Jack Morgan knew how to run his businesses and owning the county’s largest supermarket was big business. Jack knew the grocery business as good as anyone, after all the Morgan Family had been in the grocery business since the 1880s, longer than they had been running a factory. Jack would meticulously review competitor’s ads and adjust his prices accordingly, in most cases going even lower than his competitors. Jack knew his customers were not immune to the lure of the new modern grocery stores, but he also knew the two things customers wanted the most, and that was low prices and quality products.

There was a time when the supermarket was shopped regularly by customers from the nearby counties of Jackson, Washington, Clark and Jefferson. Jack hired excellent store managers in men like Joe Mudd and Elmer York, which both were clear on Jack’s mission of keeping prices affordable and customers happy. He sold his American Beauty products in the store at low prices, which drove competitors crazy in nearby counties.

Jack’s father I.C. Morgan had opened a cafeteria in the grocery store in the 1920s and in the 1960s the cafeteria was still going strong. Meals were inexpensive and very good, and I.C. Morgan rationalized if customers came for a meal, they may buy something from the store too. Jack Morgan like his father loved the grocery business and was highly successful in the supermarket arena for over 50 years.

1970s

A new decade brought even more challenges as a poor economy forced the company to change directions. Jack Morgan at this point, did whatever it took to keep the company going. New business was brought in without the opportunity for profit, old business was held onto at little profit. Jack’s goal during this time was two things; keep production lines running and provide a steady paycheck for employees. Jack knew what his company meant to the town, and he felt personally responsible to the families of his employees. In the past and early in his career Jack could rely on the experience of his father and grandfather. After that Jack relied on his business education from USC and his own experiences. But this problem was different, the economy wasn’t persuaded much by education or experience, so Jack did the only thing he could do, operate on a gut feeling based on everything he knew about the business. Never in the company’s storied history was so much at stake, and Jack soon realized the company was in need of change and perhaps a new face.

Jack began to work closely with his son John Morgan. Jack named John company president in 1974 when John was just 27 years old. John, a University of Cincinnati graduate was well versed in the operations of the company, as like his father he grew up in the plant. John however knew these were tough times for the company and for now the glory days were a thing of the past, Morgan Packing Company continued fighting the worse economic times of its history.

Even though labor disputes weighed heavily on company officials, Jack did not seem to get tired of his ongoing confliction with union forces. Even with the economy in poor condition in the early part of the 1970s Morgan Packing Company still offered plenty of work during the pack season. Jack and company officials were surprised when many positions went unfilled during the open hiring season. Jack was well aware that some of the jobs were hard difficult positions, but he knew plenty of people that needed work in the area. When the positions remained vacated Jack transported migrant workers up from Mexico, and built a camp with small apartments to house them on Christie Road in Austin.

Once again labor issues arose and complaints were filed against Morgan Packing Company for unfair labor practices. When investigated the government found no wrong doings on the part of Morgan Packing Company and the migrant workers returned for several years after that.

The final year for the migrant workers was also the last real clash with the union for Jack Morgan. In 1977 now 71 years old Jack had to deal with another ugly eight-week strike. And once again strikers reacted violently when they felt they weren’t being heard. Tensions were high in the community with all eyes on the situation. Some management personnel had their cars turned over with them in it by strikers at the entrance gate. Company property was being vandalized and the security office was shot at from a far distance in the middle of the night. One afternoon strikers sent word that no office personnel would be allowed to leave the facility without having to fight. Jack was very concerned about the office staff, most of them obviously scared. It didn’t take long for Jack to summon the Governor of Indiana Otis Bowen for help, as the Scott County Sheriff’s office seemed unwilling and incapable of resolving the issue.

After a few frightening hours help arrived in the form of the Indiana State Police riot squad. Dressed in full riot armor over 70 state troopers marched up High Street in Austin, to the factory entrance where strikers rushed away. The riot squad remained in the area for several days before the strike was finally settled.

By the late 1970s Jack and John Morgan were forced to do everything they could to keep Morgan Packing profitable. This meant closing the outside plants which were costing millions each year in taxes and maintenance. As John Morgan took on more control of the company, he headed into the 1980s with a lot uncertainty.

1980s (Jack Morgan Saves the Train Depot)

Jack Morgan was fond of supporting local charitable groups and was willing to take up their cause, even beyond financial contributions as was the case in the early 1980s for the Austin Lions Club. Jack believed that Morgan Packing Company owned the old train depot that had been sitting vacant on the company’s property for years and wanted to donate the building to the Lions Club as a meeting hall. This set off a series of legal disagreements between Jack Morgan and the Railroad Company which believed they owned the structure and wanted to tear the building down. Eventually the two parties sued each other in an effort to determine the legal owner.

Jack was determined not to lose this fight, and one night attended a meeting at the Lions Club to update the group on the status of the lawsuit. Jack was never one for holding back his words and when he was asked what he thought the outcome would be, he responded in typical Jack Morgan fashion. Speaking in his gravelly voice he told the packed-out audience in the depot that he planned on winning the case. “My father told me a long time ago the way you win these cases is to keep suing each other and hope the other son of a bitch dies before you do. I hope I can last longer than the damn railroad, but if not, I want you guys to keep suing them.” Of course, the crowd burst out laughing and Jack enjoyed the spotlight, telling them even further, “If they own the damn building, they owe me a hell of a lot of back rent for letting it sit on my property all these years.” As he believed he would Jack won his fight with the railroad and donated the building to the Lions Club, where it is now a charming showcase for the town of Austin.

Jack Morgan’s Last Fight – Legend Passes Away at 78

With John Morgan leading the way the company took on a new vision. John realized the plant was in need of many changes and he was willing to make them. He invested in new equipment and hired individuals with strong backgrounds in quality and the canning industry. He also realized the market was changing and directed the company to focus on the production and promotion of soups and offering their products to grocery store chains who wanted their own private label.

Jack Morgan was very pleased and proud with the direction John was taking the company. He seemed to enjoy the peaceful and quieter days without the ongoing labor disputes. John opened communications more frequently with union leaders and issues were less eventful. His leadership style was different than his father’s but just as effective. John supported a collaborative style of management while Jack believed only one person was in charge, himself.

By 1984, John Morgan had led Morgan’s back into a strong place in the market. For Jack Morgan the company’s turnaround continued to give him peace of mind despite poor health. Jack was now fighting his greatest battle, pancreatic cancer, and just as he had fought so many other obstacles in his life, he fought long and hard. Just short of his 79th birthday, Jack Morgan passed away on March 24, 1985.

A few days later funeral services were held for the legendary figure as thousands reached out to the Morgan family, both locally and from across the country. Even his adversaries honored him and despite all of the labor battles it was obvious, there was great respect and admiration for him among union leaders.

A trademark started in Austin by Jack Morgan in the 1930s, is the blowing of the Morgan Packing Company Whistle, which sounds like that of a steamboat and can be heard for miles. On the day Jack Morgan was buried, company officials sounded the whistle as his last rites were being read at a nearby cemetery. It was a cool, overcast spring day and as the whistle mournfully sounded in the background, an eerie silence fell across the town; Jack Morgan was gone.

Mid 1990’s Photo – John Morgan was just 27 years old when his father named him President of Morgan Packing Company in 1974.

Author: Mike Barrett (2003)